Using oak in timber wall construction...

The use of timber in external walls as a structural frame is nothing new and has been used for centuries, typically in barns and churches. They are also used, for example, where they are the frame for a bay window or porches (see photo) with the use of timber posts instead of masonry or stone piers. These frames are limited in size but nevertheless need careful consideration at the design and construction stages from a building regulation point of view. We expect our buildings to be structurally sound, fire safe, thermally efficient, and watertight.

This specific type of construction in new habitable buildings is bespoke and as such not a common form of construction and may be seen to be used as a vernacular form of construction in terms of small scale and limited location.

From a building regulation point of view we would therefore advise that specialist advise is sought and consideration is given to both local planning policies and warranty providers conditions for cover where timber construction is proposed at design stage.

LABC Warranty - Using Oak in Construction

When we consider the properties of timber in wall construction, in terms of the Building Regulations several questions are posed:

- How does the frame perform structurally, are the fissures and cracking that may be apparent over time an issue?

- How should fire resistance be considered?

- Is the timber resistant to attack by fungi/insects and how do we consider weather resistance?

- How do we meet the ever-important aspects of thermal efficiency?

Structure

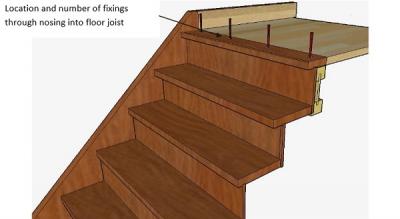

Any structural timber frame should be assessed by a competent structural engineer. Oak becomes harder and stronger as it dries. Oak is naturally low in weight but high in density and in the case of oak there may well be creep deflection as during the drying phase, the timber may split/shrink or distort. The joints should be designed to “tighten up” as it dries – so again the structure needs to be designed by specialists.

Fire resistance

European oak is denser than the average structural softwood and structural design codes therefore permit advantage to be taken of a slower charring rate. For example, BS EN 1995-1-2 (Ref: 21) cites a rate of 0.5 mm/min for European oak. Any exposed timber will need to period of fire resistance vary with the building’s purpose group and height and whether the element is loadbearing. Any load bearing elements such as structural, beams columns will need to refer to Approved document B, Appendix B for the relevant periods of fire resistance.

If in the case of a dwelling house (not exceeding 3 storeys or 24m in length) the exposed timber is adjacent to a boundary, there are also requirements for external fire resistance and reference will need to be made to Approved Document B for unprotected areas.

Surface spread of flame

If the internal faces are exposed and are within a circulation space, then a C-s3, d2 classification is required, small areas in rooms can meet the lower rating of D-s3, d2.

Each case will need consideration regarding the location and area of the exposed timber faces.

Weather resistance

When we consider external walls Approved document C2 considers the building regulation requirement that the walls of the building shall adequately protect the building and the people who use the building from harmful effects caused by:

a) ground moisture

b) precipitation including wind-driven spray

c) interstitial and surface condensation

Approved document C also considers that cladding may be weather resisting and can included natural stone or slate, cement-based products, fired clay and timer. Where we consider to external use as a timber cladding any through wall construction will need careful consideration and may need to be isolated from the waterproof envelope.

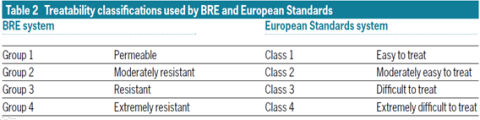

Reference is then made to other documents as an appendix to Approved document C to BRE Digest 429 (April 1998) considers the natural durability of timber and the resistance to preservative treatment. (Table 2 below)

The digest also considers in Table 3, the timber species:

Identifying green, air dried (seasoned) or certified kiln dried oak.

Where timber has been dried and has a moisture content less than 12%, it will usually be marked with a stamp saying “DRY” or “KD” (for kiln dried), however, if timber has been cut or machined, it is likely these stamps are not visible, in such circumstances, proof of purchase confirming that timber is kiln dried should be provided.

The timber needs to be appropriately seasoned and dried prior to use and the relevant standards outlines the following:

- Green oak - recently felled oak with a moisture content typically between 60%-80%

- Air dried (seasoned) oak - naturally stored oak with a natural seasoning process moisture content up to 30%

- Certified kiln dried oak - processed seasoned timber with a moisture content of 12% or less

If a coating is applied to the green oak frame, ideally the external coating should be more vapour permeable than the internal coating, as this will assist with limiting interstitial condensation. This concept is like a timber frame building, which has a VCL on the inner face and a breather membrane on the outer face.

Thermal Performance

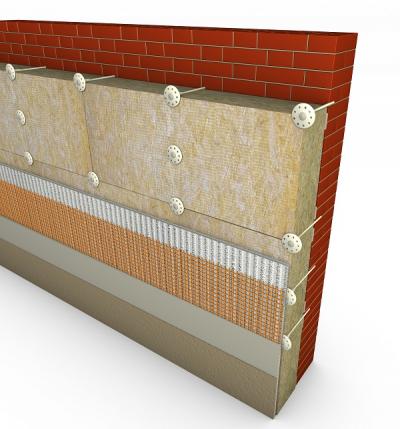

When assessing U values for external walls that incorporate a timber oak frame there is also a need to consider thermal bridging. Timber is a natural insulating material. The organic, cellular structure of timber means that it has tiny air pockets inside the timber that act as a barrier for heat and cold. This means that hardwood timber have useful insulation properties, Timber has a low U-value, and high R-value. When considering construction joint details, they will need to be calculated by a suitably competent person following the guidance in the Building Research Establishment’s BR 497 and the temperature factors set out in the Building Research Establishment’s Information Paper 1/06.

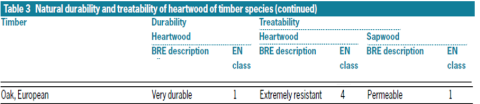

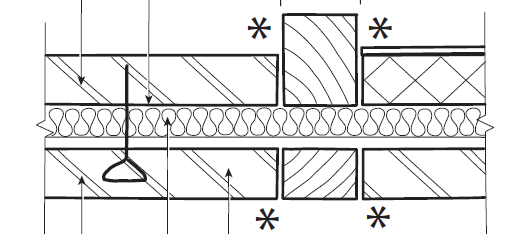

Diagram from Trada "green oak in construction" framed cavity walls

The term thermal performance does not simply cover the thermal resistance (U-value) of the structure, but also includes the vital considerations of condensation control, both on surfaces and interstitially (within the construction), and of air tightness.

Further reading/references:

Trada Wood information sheet WIS 2/3-65 Principles of green Oak Construction

Trada Wood information sheet WIS 2/3-10 Timbers- their properties and uses

Green Oak in construction (Trada, Forestry Commission publications ISBN 1 900510 45 6)

NOTE: Every care was taken to ensure the information was correct at the time of publication. Any written guidance provided does not replace the user’s professional judgement. It is the responsibility of the duty holder or person carrying out the work to ensure compliance with relevant building regulations or applicable technical standards.

Sign up to the building bulletin newsletter

Over 48,000 construction professionals have already signed up for the LABC Building Bulletin.

Join them and receive useful tips, practical technical information and industry news by email once every 6 weeks.

Subscribe to the Building Bulletin

Comments

Add new comment